“As a well-spent day brings a happy sleep, so a well-employed life brings a happy death.”

-Leonardo Da Vinci

When Leonardo talks about a well-employed life, he doesn’t meant a stable job at a respected company. Instead, his maxim touches on the need to spend your time on things that truly matter. After reading Walter Isaacson’s biography Leonardo da Vinci, I’ve put together a list of things I learned from Leonardo da Vinci. Because he certainly led a well-employed life.

1. Don’t let things outside of your control impact your potential.

Leonardo da Vinci is universally regarded as one of history’s greatest artists, thinkers, and embodies the term Renaissance Man. But Leonardo didn’t live the charmed upbringing you would assume. He was born “illegitimo”, his parents unmarried and raised by a combination of parents, uncles and family friends. “Leonardo had almost no schooling and could barely read Latin or do long division”, describes Isaacson. He wasn’t allowed to be trained in his father’s profession as a notary because his parents weren’t married.

I find Leonardo’s lack of formal education and non-traditional family reassuring. Leonardo didn’t rely on the status of his family or a top notch education to define his potential. Instead, he fostered an insatiable curiosity to catapult himself to the man he would become.

2. Be constantly curious and dig deep into that curiosity.

Leonardo was a genius. No, not a genius painter, or scientist, or engineer. Sure, he was world-class at all of things. But when you look at why Leonardo was world-class at those things, it’s because to one thing: his curiosity. He had a genius curiosity and made it his life’s work to dig deep into those curiosities.

Isaacson summarizes it well: “His genius was of the type we can understand, even take lessons from. It was based on skills we can aspire to improve in ourselves, such as curiosity and intense observation.”

Born shortly after the invention of the printing press, da Vinci benefited from the knowledge gained from reading other people’s experiences. But while he appreciated learning from other’s discovery, he valued personal experience above all. “My intention is to consult experience first, and then with reasoning show why such experience is bound to operate in such a way.”

“By allowing himself to be driven by pure curiosity, he got to explore more horizons and see more connections than anyone else of his era,” explains Isaacson.

Leonardo’s to-do list gives us a glimpse into his daily pondering and the level of curiosity we’re dealing with. Things like “calculate the measurement of Milan and Suburbs”, “get a master of hydraulics to tell you how to repair a lock”, and “ask about the measurement of the sun promised me by Maestro Giovanni Francese.”

My gut reaction after witnessing this level of curiosity is to feel embarrassed. It makes my to-do list of “buy paper towels” and “write a blog post about Leonardo da Vinci” feel pretty lame. But pushing aside the direct comparison, Leonardo’s lists is an inspiration. How can I be more curious in everyday life and how can I dig deep into those curiosities.?

3. You don’t have to be an expert in just one thing. Learn new skills.

If someone asked you what Leonardo da Vinci “was”, what would you say?

A painter or artist, right?

The funny thing is that Leonardo listed painting dead last in his skill set self-evaluation.

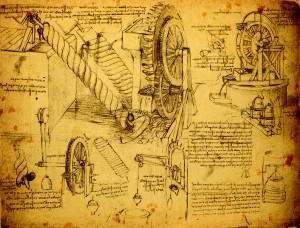

When da Vinci turned thirty, he wrote a letter to the ruler of Milan describing his skills. Think of it as da Vinci submitting a resume for a new job. Across the first ten paragraphs he proclaims his ability to “design bridges, waterways, cannons, armored vehicles, and public buildings”. Only as a footnote the eleventh paragraph, Leonardo wrote “likewise, in painting I can do everything possible.”

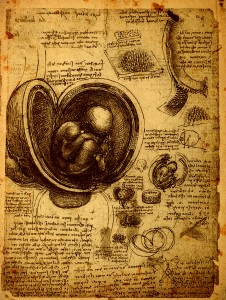

Throughout his life, da Vinci explored a wide range of studies, including “anatomy, fossils, birds, the heart, flying machines, optics, botany, geology, water flows, and weaponry.” Isaacson classifies him as the “archetype of the Renaissance Man” and I couldn’t agree more.

How can we put this into practice? If you’re in college, try to study across multiple disciplines. Pair that biology major with a business major. Studying engineering? Why not expand your learnings to the arts. Out of college? Don’t limit your learnings to that in your immediate field. Always be on the lookout for new skills to learn.

Also consider where you live. Does your community have a culture of expertise that spans multiple disciplines? It’s not just a matter of living in a big city. Some big cities focus on a single industry while smaller ones have a wider range of experience.

Consider Florence in da Vinci’s time: it had only 40,000 inhabitants but a unique breadth expertise. Isaacson describes the city and it’s approach to collaboration: “This mixing of ideas from different disciplines became the norm as people of diverse talents intermingled. Silk makers worked with goldbeaters to create enchanted fashions. Architects and artists developed the science of perspective. Wood-carvers worked with architects to adorn the city’s 108 churches. Shops became studios. Merchants became financiers. Artisans became artists.”

4. Learn from everyone.

The people around Leonardo served as both a stoker to the fire of Leonardo’s curiosities and a way to satiate those burning questions. Leonardo maximized his ability to learn by associating with fellow deep-thinkers and finding a way to learn from every encounter.

“Unlike Michelangelo and some other anguished artists, Leonardo enjoyed being surrounded by friends, companions, students, assistants, fellow courtiers, and thinkers. In his notebooks we find scores of people with whom he wanted to discuss ideas. His closest friendships were intellectual ones,” describes Isaacson.

But da Vinci wasn’t satisfied with learning from only his close friends. “He would grill people from all walks of life, from cobblers to university scholars, to learn their secrets,” says Isaacson.

Always be on the lookout for people you can learn from.

5. Don’t be afraid to be your true self

Leonardo wasn’t “normal” by societal standards and he didn’t give a damn.

Leonardo was ”…illegitimate, gay, vegetarian, left-handed, easily distracted, and at times heretical,” explains Isaacson. You might think someone like this would keep a low profile in the 15th century. Not Leonardo.. He “liked to wear rose-colored tunics that reached only to his knees even though others wore long garments.”

There are two important lessons here.

- Don’t be afraid to be yourself. I think da Vinci’s comfort with his true self allowed him to unlock his creativity.

- Let other people be themselves. If Leonardo lived in a time or place other than northern Italy during the Renaissance, including many places today, he would have been cast aside as an outcast. Isaacson highlights the importance of letting others be themselves: “Florence flourished in the fifteenth century because it was comfortable with such people.”

So be like Leonardo and be your true self. But just as importantly, let others reach their own potential by expressing their own identity.

6. Write it down and share what you write.

My friend Ethan and I used to say “write this down” whenever someone said something funny or interesting with the hopes of remembering it forever. Guess what? Neither of us wrote much of anything down. The result: fragmented memories of our experiences.

Da Vinci wrote it all down. His thoughts, sketches, and observations were recorded in his now-famous notebooks of which 7,200 pages still survive today. It’s easy to think that since much of what we do today is recorded digitally it will exist indefinitely into the future. Writing Steve Jobs’s biography, Walter Isaacson has a unique perspective on this false assumption:

“The more than 7,200 pages now extant probably represent about one-quarter of what Leonardo actually wrote, but that is a higher percentage after five hundred years than the percentage of Steve Jobs’s emails and digital documents from the 1990’s that he and I were able to retrieve.”

The second part of this lesson is to share what you write. This lesson was learned based on one of da Vinci’s shortcomings. His notebooks contained a trove of discoveries that didn’t make it’s way into the public realm until decades or centuries after their writings. Numerous anatomical, engineering, and artistic discoveries made by da Vinci were not widely known because he was not enthusiastic at publishing his work. It was a catch-22 of his curiosity. He moved onto new topics before his thoughts were organized into writings that could be consumed by the masses.

Isaacson describes Leonardo’s process as, “more interested in pursuing knowledge than in publishing it. And even though he was collegial in his life and work, he made little effort to share his findings.” Moreover, “although [Leonardo] would occasionally let visitors glimpse his work, he did not seem to realize or care that the importance of research comes from its dissemination.”

So be curious, but also take the time to share your results with the world.

7. Appreciate Nature

“Though human ingenuity may make various inventions, it will never devise an invention more beautiful, more simple, more direct than does Nature; because in her inventions nothing is lacking and nothing is superfluous.”

-Leonardo da Vinci

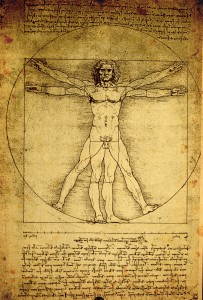

Da Vinci spent most of his life dreaming up incredible feats of human ingenuity: flying machines, armored vehicles, and the ideal city design to name a few. Yet he found true inspiration from nature’s simplicity. In fact, many passages in his notebooks draw parallels between man and nature. “Man is the image of the world”, he wrote.

But simply saying that da Vinci found inspiration is a poor description of how he viewed man and it’s place amongst nature. Leonardo did not simply classify nature and man as separate entities loosely impacting each other – they were deeply intertwined. Nature was the foundation of man.

8. Nothing is ever finished. Continually improve upon the old.

Leonardo was notorious for never quite finishing the ideas and artwork began in his notebook. To call him a perfectionist would oversimplify his approach. The early Leonardo biographer Lomazzo explained, “[Leonardo] never finished any of the works he began because, so sublime was his idea of art, he saw faults even in the things that to others seemed miracles.”

This was extremely frustrating to both the Renaissance patrons who paid for finished pieces da Vinci art and the modern day historians who dream to see his notebook pages come to life. It would be easy to see this as a negative in today’s world of “ship it’ and “don’t let perfect get in the way of good.” Most of the time I agree with these modern principles.

But I also agree with Isaacson’s take on the issue: “[Leonardo believed] there was always more he might learn, new techniques he might master, and further inspirations that might strike him.”

As da Vinci’s curiosities were satiated, he learned new techniques that could be applied to old ideas. It was common for his notebook pages to have scribbles in the margins years later with updated thoughts and modifications.

We know more than we did yesterday. So use that to your advantage and continually build on your earlier work.

9. Don’t worry about what you’ve accomplished so far.

It’s easy to look back 500+ years at da Vinci’s body of work and assume he always had life by the horns. But combing through the details of his life paints a different picture. Isaacson explains:

“As he approached his thirtieth birthday, Leonardo had established his genius but had remarkably little to show for it publicly.”

And yes, if I’m being honest, I may have included this lesson to make my 32 year-old self feel better that Leonardo wasn’t Leonardo until he was well into his thirties. But on a less personal level, da Vinci struggled through most of his life to find patrons to fund his life (translation: he sometimes struggled to pay the bills).

So just because you haven’t reached the height of your envisioned success today doesn’t mean you never will. Because maybe you’re a little more like Leonardo than you think.

Subscribe to stay up-to-date with my latest posts. I’ll send you an email after each post is published, about once a month.